I think that to have a dialogic identity is to be double in the same sort of way. When I am speaking in a dialogue, I know who I am. People turn and look at me, frowning in puzzlement or nodding agreement. At that moment I am clearly located as a speaker. But then when others respond to what I say and I listen to them I find myself, at least to some extent, identifying with what they say even when I know that I probably disagree with it. When I was speaking I might have felt convinced by what I was saying, but now that I am listening to other voices I hear the echo of my own voice as just one alternative amongst others. When I am speaking I am often trying to express as best I can what I think is the truth of the matter but I am also aware in the background that there are always other voices, other ways of looking at it, and that nagging awareness prevents me from being too sure in the way that I present things and leads to a more tentative, provisional, and open style.

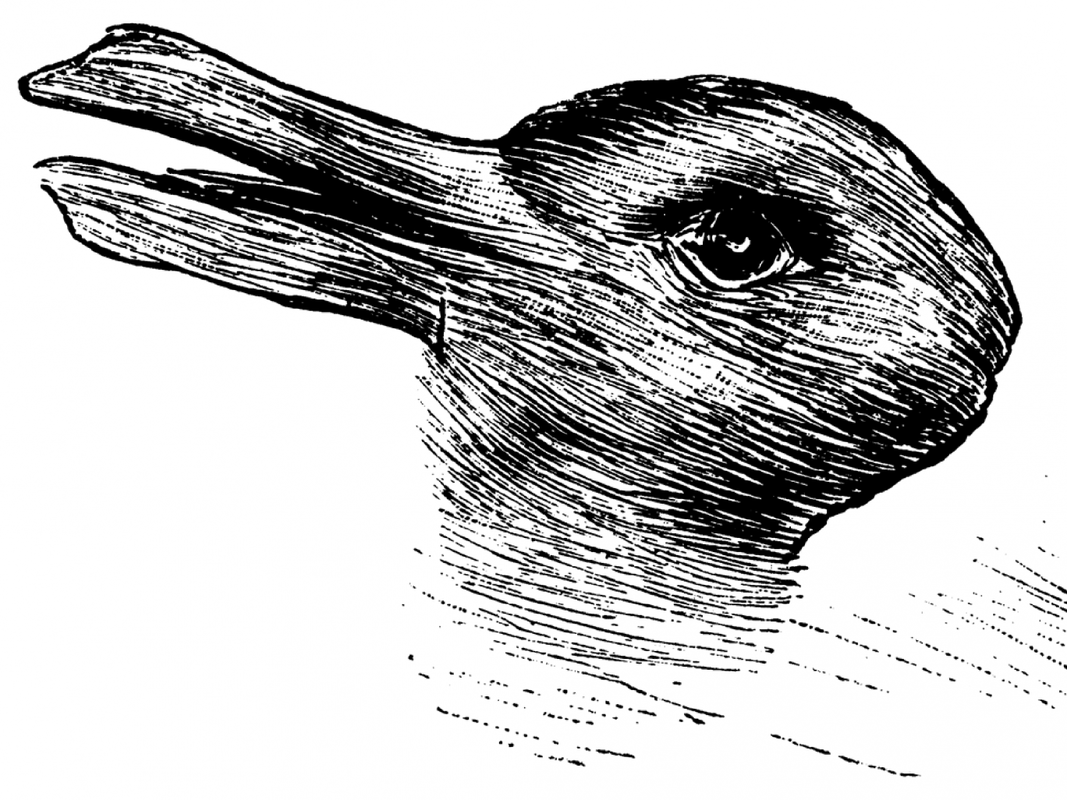

A more dialogic person is a person who identifies both with being a position in a dialogue and with the dialogue as a whole. When they add to the dialogue they often identify with themselves as a speaking voice but when they question their own ideas and are able to learn new things that is because they identify with the dialogue as a whole. As with the duck-rabbit picture, although we see both things and identify with both things we cannot do so at the same time. When we are speaking we tend to identify with ourselves as a voice and not with the dialogue. When we are in listening mode we tend to identify with the dialogue as a whole rather than with our own voice. But in listening it is important not to forget that one has a voice and can question and indeed challenge everything that one hears. And in speaking it is important not to forget that your voice is not the only voice. However convincing it may sound to you in that moment.

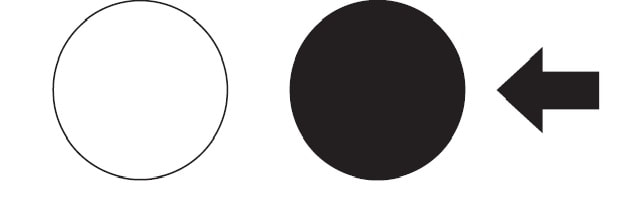

Experientially I find this kind of double identity very interesting and very odd. It is like always being on two sides of everything at the same time. Being on one side looking out at the world thinking I see stuff while secretly knowing that really I am also on the other side looking back at myself from the darkness and the invisibility that lies behind everything that I think that I see. Perhaps it is a bit like a dialogic relationship between the conscious mind, this little circle of light made up of things that I know that I am aware off, and the much larger so-called unconscious mind which is aware of so much more and which I know that I also am and simply have to take on trust. Every action relies on that dialogue and that trust. It is not really possible, for example, to speak in a dialogue, if you have to know in advance what you are going to say every time you open your mouth. Yet often people have the experience that when they open their mouths they say something unexpected but interesting, something that contributes to the dialogue and even perhaps something new that adds to the dialogue that they had no idea in advance that they knew.

Dialogism is often put forward as a contrast to monologism. Indeed it is possible to outline their differences in a table.

| Monologic Only one voice (mono-logic) Reduction of difference to one true perspective Closed meaning Certainty Totality of a closed system Knowledge as representation of otherness | Dialogic More than one voice in play (dia-logic) Expansion of awareness of see potential new perspectives Open meaning Uncertainty Infinity of an open system Knowing as relationship with otherness |

Levi-Strauss, the French social anthropologist, argued that the human mind always has to think in contrasts like this even when they not really very useful. We can only understand dialogic as a contrast to monologic but this is still quite misleading. The doublesness of a dialogic identity always has to include monologic within it.

Buber begins his classic work I and Thou (first published in 1923 and translated to English in 1937) with the claim that “man is twofold”, and draws our attention to the two fundamental modes of being: ‘I-It (‘Ich-Es’) and “I-Thou” (‘Ich-Du’). The I-It mode generates a world of objects blocking the view such that we often find ourselves trapped within it. The I-Thou mode on the other hand leads us into the presence of another person. He explains that being in relationship is a very different kind of being from the being of the It-world – the world of things. Whereas the realm of I-It is fragmented, one thing next to another, one he, one she, one it, etc, the realm of I-Thou is an experience of wholeness.

While Buber is often taken as focussing on the importance of the I-thou mode of being he is actually saying that both modes are essential. As well as being able to be called out by relationships we are also objects that can be located and labelled. Both are true. In fact it may be that the real learning of learning dialogues occurs not between different voices but precisely in the dialogue between the openness of the dialogic space and the apparently fixed context in which it occurs. This dialogicality between a dialogue and its social and historical context is often referred to as the double-dialogic (e,g Linell, 1997).

So to be truly dialogic is not to oppose monologic but to incorporate it into a higher dialogic. A good dialogue does not consist in everyone saying ‘well I don’t know – what do you think?’ Often it requires that each individual speaker makes an effort to defend a coherent position as ‘true’ making sure it is as consistent as possible. Einstein’s general theory of relativity was a great contribution to physics in this way. But of course he knew, even as he put the final full-stop on his manuscript, that his theory was not the final word on the matter but just a voice in an endless ongoing dialogue.

The multi-levelled doubleness that comes from identifying with dialogue.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed