1.The idea of crossing disciplinary boundaries

A few years ago, in a research team meeting for an education project, I raised the issue of reflection in learning and Lindsay Hetherington, a lecturer in science education, commented that Karen Barad – a feminist philosopher and quantum theorist - criticised the metaphor of reflection preferring the more complex metaphor of diffraction. That evening I looked up Barad up on the internet, watched a You Tube video, became interested and bought her book ‘Meeting the Universe Halfway’ via Amazon. Now I am trying to apply her ideas to education. Did Lindsay have agency there in causing my learning? Was she my teacher? Does it matter to your answer if Lindsay had the intention to teach me or not? Barad argues that agency is not an attribute of people: ‘.. agency is a matter of intra-acting; it is an enactment, not something that someone or something has. It cannot be designated as an attribute of subjects or objects (as they do not pre-exist as such).’ And indeed it is true that it is only after I observe the event of learning – my learning about Barad’s quantum-physics based philosophy in this case - that I can go back and trace its causation and try to attribute agency. That agency is distributed and complex including You Tube, the Internet and the material book that I bought and also perhaps the larger systems (my job, my background in the current political economy etc) that enabled me to read it and have time to think about it.

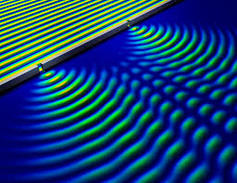

Quantum theory describes the behaviour of sub-atomic particles so it might seem quite a stretch to apply this to education. At best such a move might be seen as loosely metaphorical in the way that people often mention wave-particle duality when they really just want to say that two different ways of looking at things both seem to have some truth in them. At worst it could be seen as a gesture towards the sort of scientific reductionism that claims that to really understand anything we need explanations in terms of the underlying physics. But I find that quantum theory helps me understand what is going on in education and this is neither as a metaphor nor as a reduction to the physical. So let me try to explain why I think that quantum theory matters.

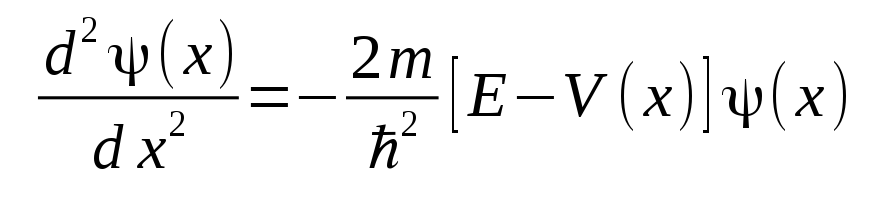

First I have to acknowledge that I cannot read quantum theory in its proper mathematical language but only after translation into my kind of ordinary language. While I can appreciate some of the elegance and significance of Schrodinger’s famous wave function – the most iconic representation of quantum theory –it speaks to me mainly as something mysterious and exotic, like an artefact from an alien civilisation.

However, once translated into prose, this formula and others seem to describe the physical world better than any other theory available in a way that implies a suspension of belief in common-sense views of time, space, causality and identity. In place of common sense we have a completely new way of thinking involving superposition, quantum entanglement, and non-local causation.

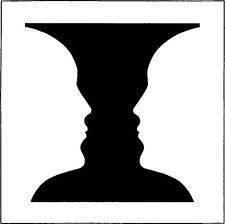

Looking at dialogues in education has led me to propose that, to understand processes of dialogic learning, we need to switch from a (monologic) ontology of identity – the idea that there are separate things such as people and words that interact – to a (dialogic) ontology of difference – the idea that differences are more fundamental than identities and constitutive of identities[i]. However, I find the idea that relationships come first, even before the things that are supposedly in relationship, is difficult to think through and certainly difficult to articulate clearly and persuasively. I mean it does not really make much sense to claim that my relationship with you in this moment (hi) is what makes you to be you and me to be me as if we did not exist before the meeting (– or does it? Who are you in this moment? When exactly did you come into existence and in what form?). Common sense thinking says that there is me sitting here in my chair and you, at some distance away, over there, reading these words that carry messages between us, messages which might cause changes in us over time depending on how we respond to them. So what fascinates me most about quantum theory is that it is a systematic and rigorous thinking through of the implications of a difference ontology in a way that is not merely of creative interest but really seems to work to help us understand reality.

It is true that theory in the field of education does not need to conform to theory in field of sub-atomic physics. However, fundamental assumptions such as the idea that meaning can be grounded on describing interactions between definable things (atoms, people, words etc) or that events are caused by physically local mechanisms (the ‘principle of locality’) are general assumptions that are not specific either to physics or to education. If one area – sub-atomic physics – has generated a set of new assumptions that work better to explain how the world works then that new way of thinking can spread to other areas by a process of transduction. Anyway, the assumptions that seem so basic to common sense and even appear to be embedded in the way we have to use language in order to communicate with each other, turn out, on closer philological examination, to be the residue of now superseded physical theories (atomism, local causation, absolute space-time etc). If our fundamental assumptions about reality originate in a physical world view we now know to be false it is reasonable to challenge their application to education by seeing what happens if we replace them with ideas that are slightly more up to date although already tried and tested over about a 100 years..

2.Dialogue and the central paradox of education

What many take to be the central problem for educational theory was outlined by Meno and re-stated by Socrates in a dialogue written down by Plato:

"[A] man cannot search either for what he knows or for what he does not know[.] He cannot search for what he knows--since he knows it, there is no need to search--nor for what he does not know, for he does not know what to look for.”[ii]

This problem has been addressed in various ways by Piaget, Vygotsky, Bandura and others. All the solutions assume the separate identity of a learner facing a world and account for how changes in the identity of the learner are caused in an essentially mechanical way by internal and external processes. Quantum theory, by questioning the assumption of separate identity at the heart of the paradox, perhaps suggests the possibility of a different approach to educational theory and so a different approach to education..

Dialogue has been put forward as one response to Meno’s paradox of how people can know things that they do not yet know. Vygotsky suggested that learners go through a ‘zone of proximal development’ where relationship with a teacher (or more able other) enables them to do things, and understand things, that they could not do or understand alone and unaided. I have tried to augment this account with the simple idea that in dialogue you do not just learn by internalising the other’s point of view but, more importantly, you also open up a dialogic space in which many (ultimately an infinite number) of points of view play. [see my earlier blog on dialogic space] Notice that this view shifts the focus from dialogues as people exchanging words in physical space-time to a more meta-physical or poetic sounding idea that the gap between people in dialogue has a certain reality.

But what exactly is the status of this ‘dialogic space’ and what exactly are the mechanisms for the learning that occurs in dialogue? Sometimes a kind of focussed collective learning occurs through dialogue which is neither about each taking on board the already formed ideas of the other nor the random effervescence of multiple new ideas that might perhaps be assumed to arise from opening up a new space of possibilities. Merleau-Ponty described this[iii]:

| A genuine conversation gives me access to thoughts that I did not know myself capable of, that I was not capable of, and sometimes I feel myself followed in a route unknown to myself which my words, cast back by the other, are in the process of tracing out for me. Merleau-Ponty, M (1968) The visible and the invisible. Northwestern University Press. | Un véritable entretien me fait accéder à des pensées dont je ne me savais, dont je n'étais pas capable, et je me sens suivi quelquefois dans un chemin inconnu de moi-même et que mon discours, relancé par autrui, est en train de frayer pour moi. |

Freeman Dyson, who made a major contribution to quantum theory, claimed to experience new ideas flowing through him. As Merleau-Ponty describes how his words seem to go ahead of his conscious understanding so Dyson, who is writing, ascribes this agency to his fingers:

“I always find that when I am writing, it is really the fingers that are doing it and not the brain. Somehow the writing takes charge. And the same thing happens of course with equations .. The trick is to start from both ends and to meet in the middle, which is essentially like building a bridge.”[iv]

Freeman Dyson found his fingers leading him on the journey of what wanted to be said even though he did not know yet what that was. It was as if the ‘truth’ (the best representation in the context) here followed him and he only recognised it after the event. I think that this is quite a common experience. It is even something that I have observed researching children solving reasoning test problems together. The more the dialogic space opens the more solutions to problems seem to emerge spontaneously. Habermas wrote, in this context, of the ‘unforced force of the best argument’ emerging out of free and fair competition between multiple ideas. But this is not how it happens. Talk and explicit reasoning are important only after the event of creativity in which a new solution emerges often fully formed or nearly fully formed. Talk and explicit reasoning of the kind defined by Barnes and Mercer as ‘exploratory talk’ are useful for sharing insights and for checking them to see if they solve the problem but this talk does not have much role in directly generating creative insights in the first place.

3. Why a neuro explanation is not enough

One direction to go in understanding the learning ahead of oneself effect or how we often already seem to know more than we could possibly know, is through the phenomenon of incubation studied by neuro science.

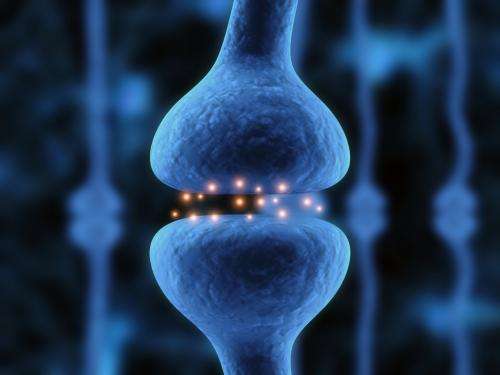

Detailed experiments into the ‘aha’ effect described by Kounios and Beeman demonstrate that the brains of participants can be observed to solve problems before the participants themselves are aware of this and so the solutions ‘pop’ into consciousness as if from outside them. This is an interesting area of research which I have described elsewhere (Wegerif, 2012, p64). However one important limitation with much supposed neuro-educational explanation is that it assumes a pre-quantum theory mechanical world-view. The assumption seems to be that thought has a material instantiation in neuronal processes that can be completely described in terms of classical mechanics. Creativity, it is claimed, forms in time within individual brains where neurons interact according to traditional mechanisms of local causation. There is an old philosophical objection to this which is neatly expressed by the point that the world is in the brain as much as the brain is in the world. But now that we are building quantum computers relying on superposition effects and quantum level effects have been found to be central to understanding even such basic biological processes as photosynthesis [https://youtu.be/_RSKI5A_lsg] it is beginning to seem unlikely that something as complex as thought has no quantum level aspect. (See Penrose, R Emperor's New Mind and https://youtu.be/3WXTX0IUaOg] )

Karan Barad, a philosopher who is also a quantum physics researcher, is, I find, a reasonably careful and persuasive guide to some of the implications of applying quantum theory to our experience of reality beyond the physics laboratory.

Step 1: Barad begins with an account of how the apparatus used to measure or observe matter can be shown to determine whether matter appears in wave from or particle form and even determine in advance the paths that photons choose to take as if they could predict the upcoming observation [see e.g https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wheeler%27s_delayed_choice_experiment].

It follows from these experiments, as Bohr argued, that any description of matter needs to include a description of the apparatus of measurement. To restate this: ontologically it is not possible to separate object from subject. Both are together in one system, called an apparatus. The exact boundaries and nature of the object and the subject depend upon the way in which the measurement is made – the ‘agential cut’ as Barad calls this. Since the apparatus is a machine for producing space and time it cannot be thought of as located within space and time.

Step 2: She argues that the apparatus has no clear boundaries. ‘Is the printer attached to the computer part of the apparatus?’ She asks and continues ‘How about the community of scientists who judge the significance of the experiment and indicate their support of lack of support for future funding?’. If the configuration of matter observed by the apparatus is called the phenomenon then each apparatus is itself an observed phenomenon for a larger apparatus. (2007 P143 p161)

Step 3: It follows that reality is made up of phenomena produced by apparatuses which are themselves also phenomena. Subjects and objects are entangled together in a single system that, as a result of each ‘agential cut’ (an observation leading to a collapse of the wave function) separate out such that a subject looks at an object. In reality this could be thought of as just one thing looking at itself which is why Barad replaces the term inter-action between observer and observed with the term ‘intra-action’. This is a relational ontology in which ‘relata only exist within phenomena as a result of specific intra-actions (i.e there are no independent relata, only relations within relations).’ P429

Socrates’ solution to the educational paradox introduced by Meno (above) was that learning new things is actually a kind of recollection. We have access to an eternal soul that knows everything but when we incarnate we forget and the role of the teacher is to help us remember.

Barad’s version of Bohr’s interpretation of quantum could perhaps be read as offering a solution which is similar. Who we think we are – finite beings often closely identified with our physical bodies - is a kind of forgetting produced by an ‘agential cut’ (the collapse of the wave function). Who we really are is the whole entangled system before the cut including material objects and other people. Educational enquiry is not therefore, on this reading, about constructing new knowledge from scratch so much as about deconstructing the gap that separates us from who we really are and so from what we already know intuitively.

But Barad is not saying that. For her there is no true ‘self’ or true ‘thing’ underlying phenomena as there are no separate things at all, only one dynamic process. This means that ‘God’ or ‘the Universe’ should not be thought of as some sort of underlying agent. As she puts it: ‘Agency is not an attribute but the ongoing reconfigurings of the world. The universe is agential intra-activity in its becoming’. The educational implication is not that we retreat passively to a state of mystical union before the cut but that we participate more wholeheartedly in the creativity of the universe which consists of making new cuts, configuring and reconfiguring the world in new ways. Ethics and responsibility is bound up with the realisation that we are, in a sense, all the others and all the possibilities of matter.

5.And dialogic education?

Barad’s theory of agential realism fits in some ways with insights from dialogic theory but is useful in extending dialogic beyond culture to incorporate the material world. We do not just dialogically construct meanings, we dialogically construct matter. But what we mean by ‘we’ here has to extend to include the material world. Let me explain.

The standard model of agency that Barad is aiming at replacing is that of an autonomous self with intentions that get realised in acting on the world. A dialogic account of agency is already not like that. Let me illustrate this with a little made up story. I have a dialogue with some friends about whether to eat Indian, Chinese or Italian food tonight. I start off wanting Indian but we end up eating Italian. I could experience that as my agency being overridden by the others, or, maybe I listened and found myself persuaded that Italian would be better. This can happen partly because the fact that someone else wants something often makes it seem more desirable to me. In dialogues there is a participation in embodied feelings as well as in abstract ideas and salivating over the prospect of a good pizza is an embodied feeling that can be transmitted. On the way to the Italian restaurant we find the road blocked by barriers around a fallen tree and so we turn to try to find a way around. In the process we come across a gastro pub with a special offer and a great aroma. We all agree that this is the best option and feel grateful that the tree falling led us to make a new discovery. This little story is meant to illustrate Barad’s idea of entangled agency that is realised only in enactment. Lots of voices enter into the final outcome in a way that is not separable and includes physical objects such as a fallen tree. But this is precisely the nature of dialogic agency. When we make decisions and act through dialogue I find that I can participate – I sometimes lead and sometimes follow - but I cannot control. When the dialogue is working I identify with it and take joint responsibility. The fallen tree begins as a barrier to our intentions but ends as a contributor to a new beginning.

Entanglements produce what Simondon called ‘trans-individual’ effects or the agency of larger wholes. This explains Freeman Dyson’s feeling that his fingers led him to express truths about quantum physics before he had understood them himself. He became entangled with the literature in the area which is also to say that he became entangled with the behaviour of sub-atomic particles. He was on both sides at once building a bridge - as he put it. His new theories were not his alone, nor were they the voice of the universe simply possessing him in order to explain itself to itself - the agency was entangled and enacted. This explains the paradox of educational dialogue and inquiry, that we can learn new things and become new people and create new worlds in the process.

The boundary between me and you in a dialogue is constitutive of the dialogue – there is no dialogue without the boundary. I have focussed a lot on that boundary in the past. But Barad reminds us that there is also a boundary with the matter of the dialogue, with what we talk about. And the tools we use to support the dialogue enter in as agentive voices in their own right, I mean, for example, the particular concept words or other technologies such as computer software. If we pause and question these boundaries and open them up into a space of possibilities and enter into that space then we are truly in dialogue. Being able to cross-over and see things from your point of view as well as my point of view is only possible because we share a ‘prior’ or ‘underlying’ space of possibilities. Similarly Freeman Dyson being able to cross over and see things from the sub-atomic particles’ point of view was also only possible because of a shared space. Einstein writes about how he formed his theories out of a kind of dialogue with the universe in which he imaginatively role-played being a beam of light and such-like. Dialogue is possible because we are not completely contained by the configured world that we experience on the collapse of the wave function. The space that opens up in dialogue – dialogic space - is a return – always partial – to the space of all the possible perspectives and meanings before the cut was made and a particular reality became crystallised. The words we use in dialogue and the many little thought experiments we use are themselves ways of reconfiguring the world in order to creatively explore its possibilities.

Applying quantum theory to education helps us to understand how dialogues can work by unpicking boundaries, opening a space of potential and allowing learners to respond to the call of flows of meaning that originate beyond them and behind them. These flows of meaning can take the form of long-term cultural dialogues – like the long-term dialogue of Mathematics mentioned in my last blog. But culture is always entangled with matter and with nature. Barad’s account of the emergent and dynamic agency that arises from quantum entanglement – agency that we participate in but do not control - perhaps also explains a flow of meaning many feel called by that seems larger than culture – as if the universe itself was seeking to know itself and to love itself through us.

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. duke university Press.

[i] Wegerif, R (2008) Dialogic or Dialectic? The significance of ontological assumptions in research on Educational Dialogue. British Educational Research Journal 34(3), 347-361.]

[ii] .Plato, Meno, 80e, Grube translation.

[iii] Merleau-Ponty, M (1968) The visible and the invisible. Northwestern University Press.

[iv] Quoted in Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New

York: Harper Perennial.

In writing this blog I was also thinking of (in dialogue with?) David Bohm's work on realist quantum theory and on dialogue, about Deleuze's work especially 'immanence: a life' and, of course, about Spinoza - 'the Christ of Philosophers' as Deleuze calls him.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed