The caricature of the transmissional teacher that was quite often mentioned in our conversations at that time I recall, was Gradgrind, a very unsympathetic character from Charles Dickens's novel 'Hard Tines' who said: “Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else. You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them". As usual in such cases this thin and inadequate representation of the 'other', is a product of what is often called 'my-side bias', the tendency to see others only in the light of one's own perspective as a shadow of it characterised by their deficits rather than by their strengths. Mea culpa.

While I value the findings of empirical educational research I interpret them within the larger interdisciplinary debate about education. My problem is, frankly, that it is just too easy to fix education research results so that they say what you want them to say. Often education research suffers from petitio principii or circular argument: the conclusions are a product of the assumptions built into the methods. After all what exactly are we measuring when we measure 'learning gains'? Learning facts? Learning how to love? Learning how to think? And how exactly do we characterise Direct Teaching? or Active Learning? Does Direct Teaching mean no student initiated questions? Does Active Learning mean no transmission of knowledge by the teacher? Even if we manage to define our terms it is still possible to implement a potentially really good pedagogical approach in a way that gets poor results. The opposite is also true, weak pedagogical strategies such as just lecturing from the front, can be done in such a way that they get good results. I have noticed that teachers who are real thinkers somehow manage to communicate how to think to their students even when all they do is lecture. On the other hand, teachers who, for whatever reason, are terrified of not having the correct answers, can fail to teach thinking effectively even when they facilitate group inquiries with the use of thinking maps and multi-coloured hats.

The serious and, in the broad sense, 'scientific', research study which has most led me to change my attitude towards Direct Teaching is not another Randomised Control Trial but an article in Mind, a prestigious philosophy journal. It is titled 'Knowledge from vice: Deeply social epistemology' and it takes a historical and social anthropological approach to the question of how we come to know things.

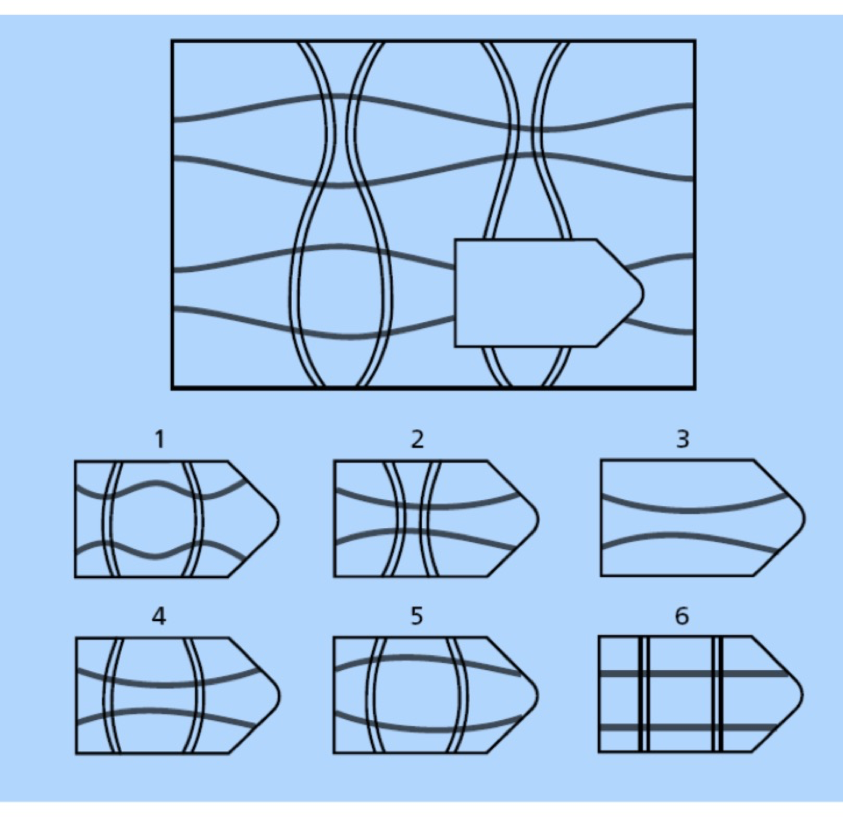

Humans are hard-wired for Direct Teaching

The message of the article is that if our ancestors had listened to injunctions such as 'think for yourself: do not follow blindly what you are told' then we would not be here.

Here is a striking example: when maize became a staple food crop in the USA in the 19th Century it brought with it many serious outbreaks of the disease pellagra caused by a lack of niacin. Amerindians who had eaten maize as a staple for thousands of years did not have this problem because they always cooked it with an alkali (ash from a certain wood) that made the maize release niacin. They did not know why they did this - they did it because the ancestors did it.

Another extraordinary illustration of this thesis is provided by Inuit clothing. Many clever people with lots of resources have tried to use a problem-solving approach to survive in the extreme cold of the arctic and failed.

The authors argue, from these and other examples, that what has been taken to be an epistemological vice, individuals not thinking critically for themselves but just accepting what they are told, is actually often an epistemological virtue. The main point is that knowledge and also 'intelligence' is primarily collective rather than individual. It is not just the Inuit who survive because of the accurate transmission of complex cultural knowledge, we all depend on this: that is what it means to be human and so it does not seem unreasonable to think of Direct Teaching as the first and most basic function of education.

Stanislaus Dehaene's account the brain science of learning confirms that humans are hard-wired for the transmission of knowledge. Eye contact from a parent or tutor puts young children instantly into what Dehaene calls a "pedagogical stance" that prepares them to learn from what they are being taught, interpreting the information imparted as a) important and b) generalisable. But we all know this really. Go into any primary school and you can see that children love to listen to stories told by teachers, and, also, that they tend to believe whatever they are told.

The problem with education as transmission of culture

Dehaene points out that our species specific biological adaptation for education in the form of Direct Teaching does not only explain why people can so easily be taught useful cultural knowledge, it also explains why people can be convinced by cultish conspiracy theories and all sorts of dangerous nonsense. In the modern age, the Internet Age, this hard-wired mechanism for the uncritical transmission of cultural stories leads to many dangers. It needs to be balanced with the teaching of critical thinking.

Fast versus slow thinking

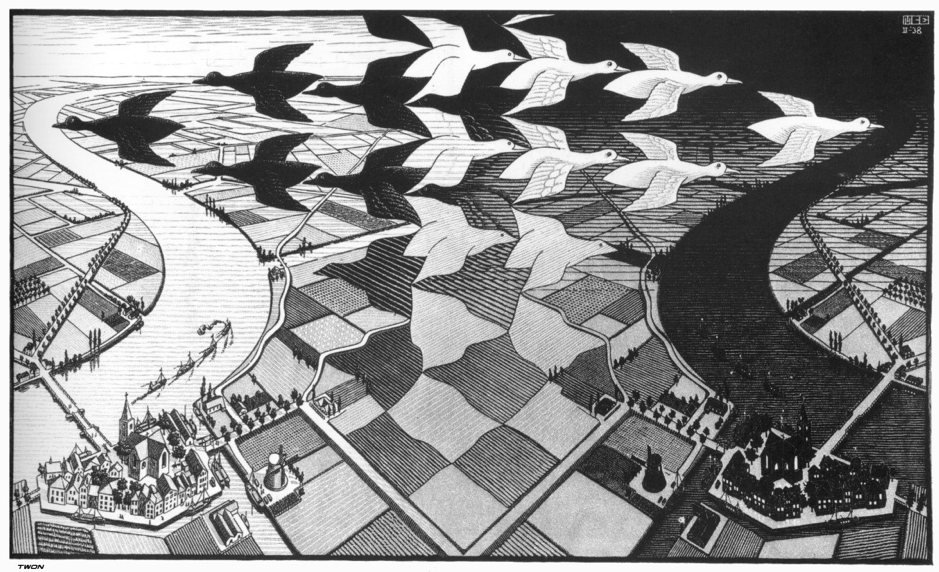

The authors of the article on 'Knowledge from vice' revel in the paradox that we depend for our thinking on the apparent vice of uncritical cultural transmission. If the common exhortation to the young to think for themselves and question everything ever really succeeded then, they claim, we would all be in serious trouble. So why, the authors ask, do we still promote the value of critical thinking?

"It takes hard work to consider a range of hypotheses and to be open-minded. It takes hard work to think for oneself. We fail at these attempts at epistemic virtue routinely. If we’re right, these failures may be happy: if we succeeded very much more often, we would do less well epistemically. But that doesn’t entail that our successes are not themselves epistemically virtuous or expressive of cognitive agency: it is, perhaps, only by great effort that we achieve a cognitive sweet spot, where we follow the crowd and are close-minded just enough"

This mirrors the research findings described by Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman in his best-selling book 'Thinking fast: thinking slow'. Fast thinking is the default, it is easy for us but full of biases. In order to correct these biases we need to step back, question our first impressions and engage in slow careful reflection and analysis. The problem is that this slow thinking takes up cognitive load. Most of the time we need to use fast thinking. While Kahneman implies that automatic 'fast thinking' is biologically hard-wired, the argument made by the 'Knowledge from vice' article is that much fast thinking has evolved within cultures and is not so much biological thinking as collective thinking.

Open versus closed society

A contrast between closed and open cultures was first made by Bergson, elaborated by Popper and has more recently been applied to education by Hanan Alexander in his interesting book 'Reimagining Liberal Education'. Education is always the transmission of a culture, but cultures are not all the same. Closed cultures, cults, conspiracy theories, and pseudo sciences, refuse to learn from dialogue. Open cultures and open societies, on the other hand, are open to learning from external dialogue with other cultures and also, perhaps even more importantly, they are open to learning from internal dialogues. In open societies reflection and criticism is encouraged because this potentially leads to continuous improvement.

Even though, in the Internet Age, we all increasingly participate in one world culture, this shared culture has many strands. While there are different cultural traditions being transmitted through education in schools in the UK and around the world the one thing which they all need to have in common, if we are to have a shared sustainable future on this relatively small planet, is openness to learning from dialogue. This requirement of openness and reflection has implications for how we teach. Knowledge needs to be taught in a way that makes it clear that it is not final and absolute, but is our best knowledge so far, always open to questioning and open to reformation. In open cultures students must to be equipped with the tools that they need to be able to question and develop the tradition that they are being inducted into.

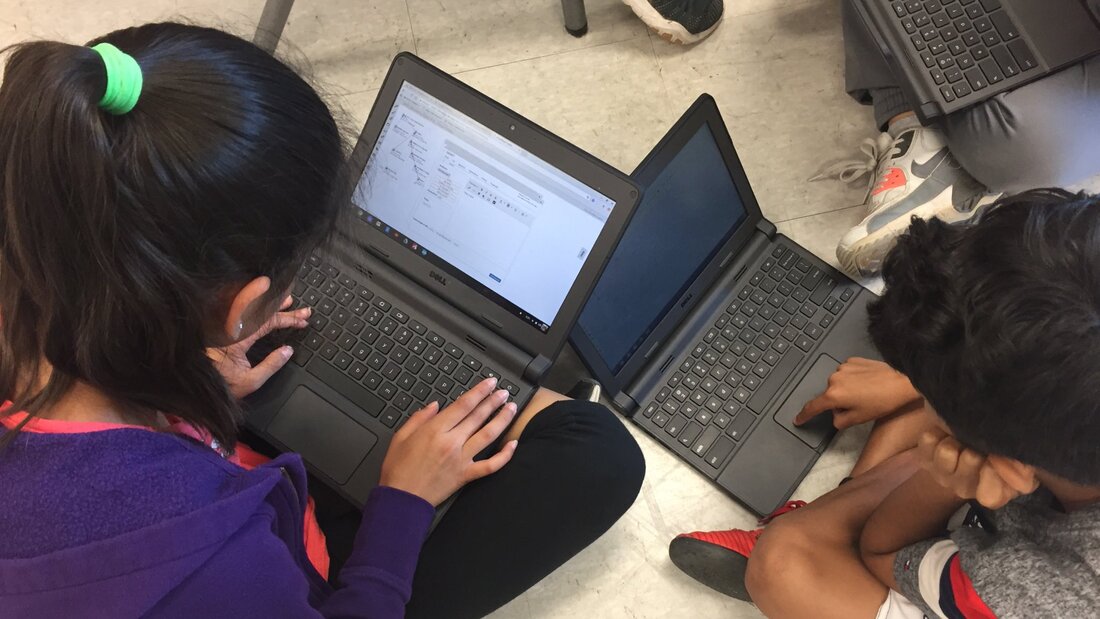

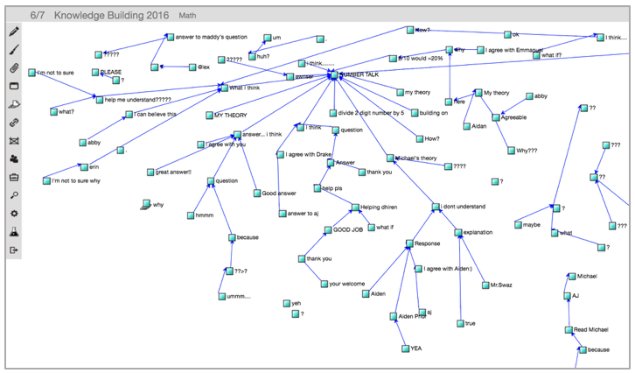

Double Dialogic

One way to resolve the apparent dichotomy between Direct Teaching and Active Learning, sometimes referred to as the war between so-called 'traditional' and so-called 'progressive' methods in education, is by acknowledging that, yes, education is all about inducting students into their shared cultural inheritance, but that, in an open culture, the cultural inheritance that is being transmitted through education includes a component dedicated to self-reflection and self-reformation. Thinking is always thinking about something. The teaching of shared inquiry and critical thinking always occurs within the larger context of transmitting a cultural tradition. The tools needed for thinking such as the language of questioning and 'ground rules for effective talk', are themselves forms of cultural knowledge that need to be transmitted through Direct Teaching.

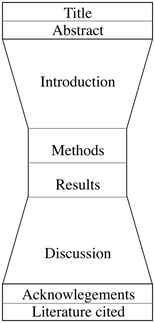

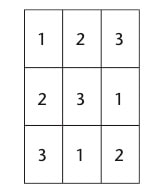

Double dialogic is the recognition that dialogues do not only involve specific speakers, say a small group of children in a classroom, they also, at the same time, involve a dialogic interaction with the cultural context. A dialogue about a science question in a classroom is not only between the different views of the children, it also has to invoke and react to the slowly changing views of the relevant community of scientists. This concept of the double dialogic can enable us to understand how Direct Teaching is compatible with dialogic education. The first loop of dialogic education is induction of children into short term dialogues in the classroom. This teaches how to form good questions, how to listen well, and how to think both critically and creatively. The second loop is induction into the much longer-term dialogues of culture. Long term dialogues of culture such as history, maths, art and science, are strands in a single evolving unbounded dialogic space that Oakeshott referred to as 'the conversation of mankind'. While dialogic education is normally understood only in terms of the first loop, as teaching children how to think together in the classroom, it should also be understood in terms of the second loop, inducting children into participation in a cultural tradition understood as itself a kind of dialogue, a long-term collective dialogue. It is not possible to participate usefully in a long-term cultural dialogue without already knowing things. Induction of students into long-term dialogues requires Direct Teaching of the dialogue so far, the scientific canon for example or the best of what our ancestors have thought and said up to now. But this must not be taught as dead, fixed, final knowledge but as a living tradition that the students can themselves participate in and perhaps take further.

In any open, living, evolving, culture, education into how to question, reflect upon and reform knowledge, is as essential as the Direct Teaching of knowledge. The 'traditional' education method of telling stories and expecting children to listen and to learn is basic to the successful reproduction of all human cultures. More 'progressive' methods that teach children how to ask questions, to reflect and to create new knowledge, are also an essential component of education in all open cultures. Direct Teaching and Active Learning are not only compatible, they require each other.

Links and references

https://www.tes.com/news/why-you-have-got-direct-instruction-wrong

Alexander, H. (2015). Reimagining liberal education: Affiliation and inquiry in democratic schooling. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Dehaene, S. (2020). How We Learn: The New Science of Education and the Brain. Penguin UK.

Fernbach, P., & Sloman, S. (2017). The knowledge illusion. Penguin Random House Audio Publishing Group.

Henrich, J. (2017). The Secret of Our Success. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan.

Kirschner, P., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why unguided learning does not work: An analysis of the failure of discovery learning, problem-based learning, experiential learning and inquiry-based learning. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75-86.

Levy, N., & Alfano, M. (2020). Knowledge from vice: Deeply social epistemology. Mind, 129(515), 887-915.

Phillipson, N., & Wegerif, R. (2016). Dialogic education: Mastering core concepts through thinking together. Taylor & Francis.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed