My first time in a school as a trainee teacher involved similar experiences. At first the other teachers made me feel at home but then small incidents led me to feel like an outsider. I did not understand the significance of many unspoken differences that I could somehow sense were important without knowing quite why. And I do not just mean which chair to sit on in the staff room – although that was an issue – I also mean most aspects of the craft of teaching. Some teachers, for example, were expert at gaining respect and directing the attention of difficult students. At first I could not see how they were doing this. Later I learnt to recognise some ways of using voice, posture, and eye contact that they were using and that I needed to learn. It almost always takes a while to move from feeling like an outsider to becoming an insider: from seeing signs of what being a teacher means when looking at others to walking and talking the reality of being a teacher from within.

We are all of us surely familiar with this switch from outside to inside – at least I hope that this distinction makes sense to you. (And if this does make sense to you, dear reader, then pause a while to consider what is happening when you read these signs, how are these patterns of external grey or black marks on a screen in front of you connecting with patterns in your experience, connecting with your answering words perhaps, to form a new internal space of meaning not just outside you as if trapped on the screen but also not completely inside you, closed off inside your head. Where is this place? This space where we meet? What is it exactly?) While most people seem to get the difference between being an insider in a social situation and being an outsider, the same people can seem to get very confused at what I think is the closely related distinction between ‘subjectivity’ and ‘objectivity’ or between ‘consciousness’ and ‘matter’.

In notebooks published after his untimely death the French philosopher of perception, and my first intellectual crush, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, describes an incident on a visit to Manchester when, perhaps thrown by the local accent, he could not make out what the taxi driver was saying. He writes that it was only when he did not understand that he thought to himself ‘those are words there’. His perception shifted. Normally if a taxi driver says something like: ‘it is a lovely day today’ we grasp the meaning immediately and are ready to respond. Normally hearing words means moving directly into a world of shared meaning. But this time he heard the words only as external sounds in the air. Objective, material facts. That is how things often appear when you are an outsider – closed off, cold, dead. But as an insider, you understand the words and you enter into a shared space, what I like to call a dialogic space. It is dialogic – meaning ‘like a dialogue’ – because all the voices and words in this space are not static and fixed objects anymore but they influence each other dynamically, moving and changing – dancing around each other in real time.

I think that what might lie behind binary accounts of objectivity versus subjectivity is an extrapolation of ideas out from the everyday experience of having an inside point of view, talking to a taxi driver for example, or taking an outside point of view, watching someone else talking to a taxi driver for example or perhaps imagining Merleau-Ponty talking to a taxi driver in Manchester. On the one hand people have projected the idea of an inside without an outside: the subjective world; a mysterious realm sometimes referred to as ‘consciousness’ inhabited by vague ghosts labelled as ‘souls’ or ‘selves’ surrounded by buzzing clouds of ‘thoughts’, ‘values’ or ‘memories’. On the other hand people have projected an equally odd, equally extreme idea of an outside without an inside: the ‘objective’ real world; a world of solid fixed things, matter made of atoms like little hard ball bearings bouncing around or fields of time and space like a four dimensional shoe box that contains us within it. But if you return from these culturally constructed fantasies to the reality of experience you will I hope realise with me, that inside and outside are always entangled up together - it is simply not possible to have an outside without an inside or to have an inside without an outside. What we have is not a choice between subjectivity or objectivity, consciousness or matter, but more a kind of dialogue or a kind of dance: sometimes I see myself as an object, defined by the gaze of others, sometimes I am on the inside looking outwards and defining them, sometimes the objects I see before me are just that, closed dead things to be probed and measured, and at other times they come alive and draw me into new worlds of experience.

Modelling the outside becoming inside

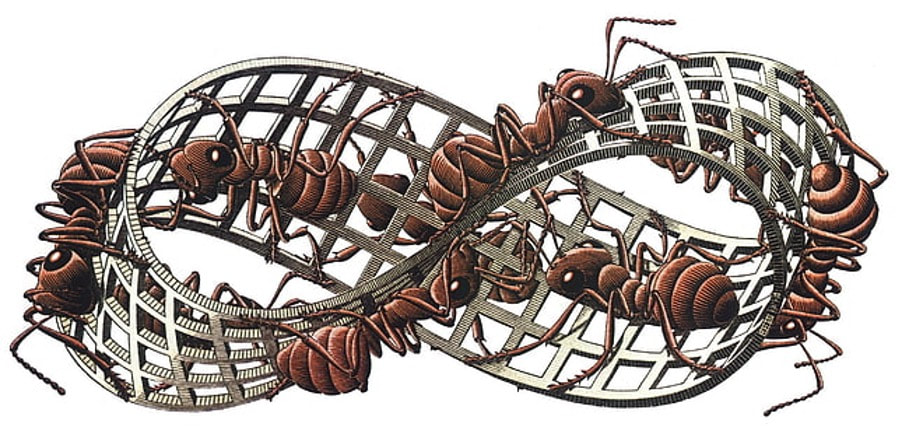

An ant walking forwards on the surface of a mobius strip would find itself moving from the outside of the strip to the inside. This could be an analogy for what happens in education: at first the strange Greek words like λόγος are alien, outside my experience, but after a while, with the help of a guide, I find that I can use them creatively to make sense of things. From being an object in the apparently external world they become lights in the more internal world of my understanding. From being an outsider I become an insider just by walking forwards on the path of education.

I hope that you agree with me that this 'turning the outside inside' idea helps to describe learning Greek philosophy perhaps or learning to be a teacher but I would also like to take it further. I think that this idea sums up what is most essential to education and it locates education as a part of what might be a much larger process of growth through which the whole external apparently ‘objective’ world or universe is slowly internalising in order to understand itself and express itself through us. Perhaps we are the universe on the inside? After all the scientists who explore the universe and discover new things work in institutions of education, their research is combined with teaching, and the same is true of scholars and researchers who explore and expand the world of human experience through history and the arts. At its best education does not just reproduce what is already there, it inducts new apprentices to participate in the endless job of the creation and recreation of the world.

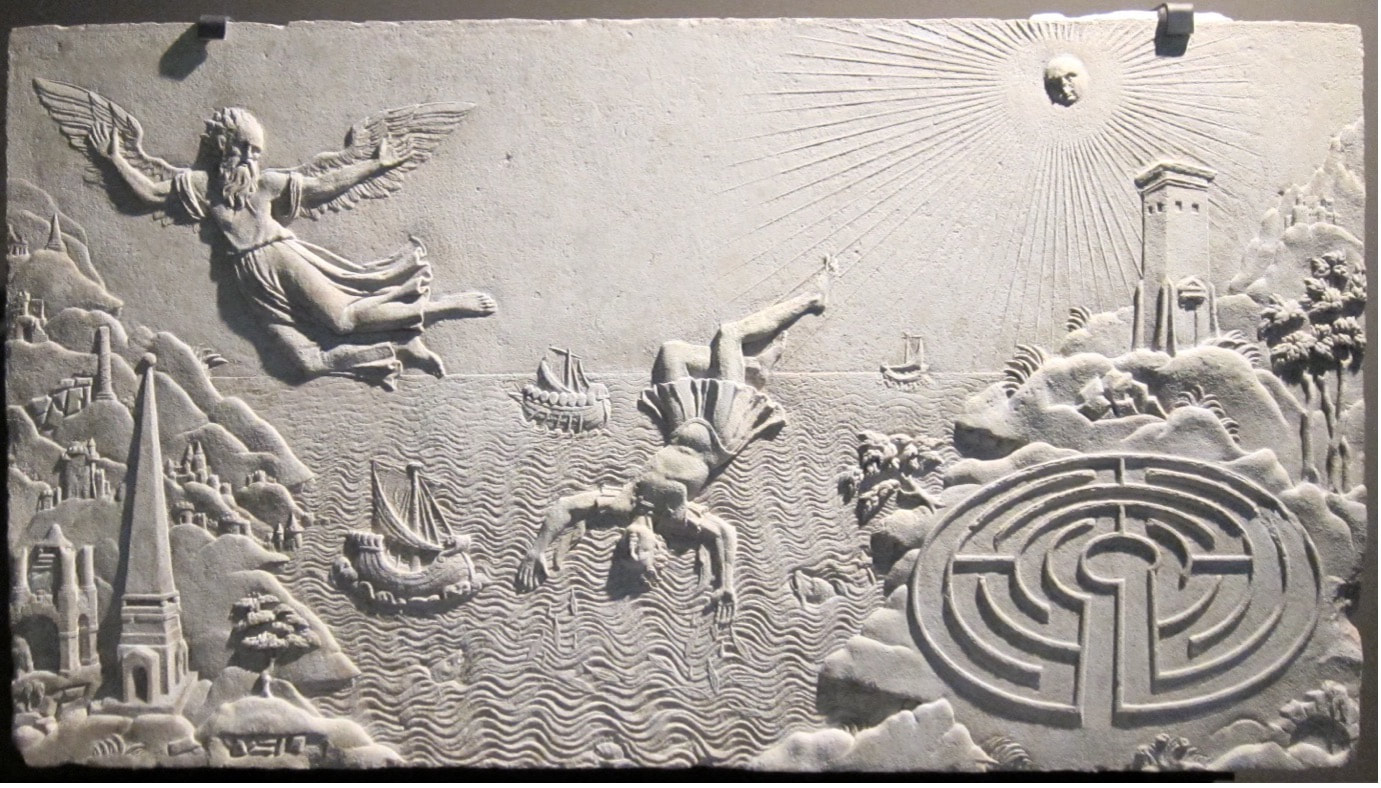

I got this big idea – the idea that education as about turning outside inside in order to be able to turn inside outside again in expression – after reading James Joyce’s autobiographical first novel ‘Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man’. I was struck by how he starts the novel with himself, the author, as a passive part of the external world. The opening words of the novel are:

Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road and this moocow that was coming down along the road met a nicens little boy named baby tuckoo. . .

I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.

27 April: Old father, old artificer, stand me now and ever in good stead.

Making sense of the role of ChatGPT in education

Although I first came across this idea of education – education as turning outside inside – in Joyce’s novel, I later found the same sort of idea in different forms within educational theory. The ‘Situated Learning’ theory of Lave and Wenger, for example, describes how outsiders join communities of practice moving from ‘peripheral legitimate participation’ (doing small jobs, sweeping the hair in a hairdressers shop for example) until they become central players, old-timers whom others turn to for mentoring and advice. The Russian educational psychologist Vygotsky articulated a related theory of education as ‘internalisation’ using the Russian word vrashchivanie which also means ‘ingrowing’. His basic idea is that everything we think of as mind, not only being able to think but also being able to be conscious of thinking, is first encountered externally in social interactions and cultural practices and then internalised. Through education children are actively taught their culture so as to be able to think with it. This means that when we look out and think things as if we are individuals we are actually the collective culture on the inside albeit expressing itself in an always unique new way. This idea that the collective becomes the individual so that the individual is the collective on the inside is also suggested by Joyce when he writes about becoming the ‘conscience of my race’.

But Joyce’s model of education offered in his ‘Portrait of the Artist’ is perhaps a bit too heroic and individualistic. He refers to forging his new conscience in ‘the smithy of my soul’ as if his soul was like a separate space cut off from the world. Another way of looking at this same process might be as him finding his voice in the larger dialogue of culture, a dialogue that includes multitudes. ChatGPT and other AI agents based on large language models (LLMs), offer what is, I think, a much clearer model, of how education can be seen as a circling of the collective outside around an individual inside and then outside again in expression. ChatGPT begins with a collective outside – it trawls the internet to collect externalised language or words that have already been spoken. It does not read these words as words but finds statistical patterns in them. When you ask ChatGPT a question to help with learning any subject – perhaps key words in Greek philosophy, or how best to engage difficult students – it draws on this vast background of collective knowledge to express an answer. This answer has meaning for you only because it is internal to the specific and unique educational dialogue that you are having at that moment. ChatGPT is not conscious and does not understand anything. Its words circle from the collective outside of (potentially) all recorded language use on the internet to the unique and specific inside experience of you the user finding that the words ChatGPT gives you have meaning for a task that you are facing here and now. The meaning element, the educational purpose, is only possible because of the human in the loop, you who are asking the question and contextualising the answer. The AI and human students form together an interesting new kind of global organism: words and other meanings expressed by unique individuals understanding things and solving problems in a context go to make up part of the collective external treasury of signs that will then be trawled and processed by the AI to be fed back to new students asking new questions in new contexts. A collective unconscious outside revolves around and is constantly expanded and recreated by many unique conscious individual insides. I think that this is a good way of understanding what is really happening in education when it works well. The collective culture turns inwards and is reborn in each individual student as their ability to think creatively and express themselves outwards in ways that contribute back to the collective culture.

Why this inside-outside distinction matters

Some accounts of education seem to remain only on the outside without giving a role to the inside – they are not taking seriously the needs of individuals and communities trying to understand the world and to find their place within it. We read for example in UK government documents that learning means changes in long term memory: the story seems to be that facts found first outside of students in books move inside into their brains and are then expressed outside again onto the exam page. If this really is education, then ChatGPT can do it better. Why not eliminate the middleman? It would be more efficient. ChatGPT can trawl for facts faster than human students and can then regurgitate these more accurately as well as weaving them together more coherently and persuasively into essays.

Real education is education for understanding which means the expansion of consciousness and the transformation of identity. Real education is about bringing what we originally encounter as external to us into an internal space of meaning, a shared dialogic space enabling us to think and to act together with more insight and more wisdom. ChatGPT and other LLMs can support this kind of real education but only when working together with human students and human teachers. To make this vision of education work we need to teach students how to dialogue with AI agents to construct answers to problems in contexts and we also need to teach them how to find together new and better questions to ask and new and better problems to pose. Education could potentially become a virtuous circle combining the collective information gathering of AIs with the individual questions and insights of students; students who are thereby engaged into a kind of game of leapfrog with this new technology using it to gain more knowledge and stimulate further insights.

Thinking about education through the lens of LLM-based AI we can see that it has always been the circling of a collective outside – the collective inheritance of a shared culture - to form individual insides able to express outwards both to recreate culture and to create new culture. But now with AI able to handle most of the more external work needed for this cycle, trawling for, processing and reproducing collective data, the focus of teaching and learning can be much more on the inside part of the cycle, on growing unique individual minds able to participate creatively as voices in a shared dialogue or what some might poetically refer to as a growing collective mind – an ever expanding noosphere (from nous or νοῦς, the Greek for mind).

Postscript

I want to end with something rather cryptic and evocative that Vygotsky wrote in the context of articulating his theory of education as internalisation or ‘ingrowing’.

Consciousness is reflected in the word like the sun is reflected in a droplet of water. The word is a microcosm of consciousness, related to consciousness like a living cell is related to an organism, like an atom is related to the cosmos. The meaningful word is a microcosm of human consciousness.[i].

[i] https://www.marxists.org/archive/vygotsky/works/words/Thinking-and-Speech.pdf page 284

RSS Feed

RSS Feed