How do we know it is real?

In the fourth century BC, Plato wrote that we are like people sitting in a cave looking at shadows cast by the light of the sun and mistaking these for reality. Chung Tzu, a contemporary of Plato in China, wrote that he dreamt he was a Butterfly and that when he awoke he no longer knew if he was a man dreaming he was a butterfly or a butterfly dreaming he was a man. In the film Morpheus prepares Neo for a new awakening with the same sort of argument:

Have you ever had a dream, Neo, that you were so sure was real? What if you were unable to wake from that dream, Neo? How would know the difference between the dream world and the real world?

The idea of the Matrix, that we inhabit a computer simulation controlled by malevolent machines, is very similar to one of the doubts proposed by Descartes that all that we take to be real is a trick played upon us by a powerful demon. Descartes’ way out of this doubt was to provide a rational argument for the existence of an omnipotent and benign God who would not allow the demon to get away with it. Bishop Berkeley, the 18th Century British Empiricist philosopher, continued in this direction to argue that everything exists only as an idea in the mind of God. Dr Johnson, the English wit and man of letters, famously responded to this theory by kicking a stone as hard as he could and claiming: ‘I refute him thus!’

But is that really a refutation? What argument or evidence, if any, would count against the claim that we inhabit a simulated reality?

When I put forward the idea that we might live in a simulation created by an alien civilisation people commonly respond: 'So what?'. If everything remains exactly the same why should our interpretation of it matter? The Matrix addresses this question and shows that, whether they articulate it or not, everyone really has an interpretation of the ultimate nature of reality and that this really does matter a lot. The common desire to fight social injustice and alleviate poverty, for example, seems hard to question and yet it rests upon an assumption about the material reality of the human condition.

In one dialogue, agent Smith, a personification of the Artificial Intelligence (AI) that now rules the Earth, tells Morpheus that the Matrix was originally modelled on human descriptions of paradise, but that this had not been accepted by their human ‘crop’, many of whom had died as a result. In response the machines created a more historically accurate simulation of human life full of pain, poverty and struggle. Humans responded well to this world because it was a world that they could believe in. The everyday struggles of life gave the humans a necessary sense of purpose. In the context of the Matrix, fighting injustice or poverty becomes absurd. Morality and compassion in the Matrix consist in calling people to awake from the dream, even if this awakening is at some cost to their apparent material comfort and health.

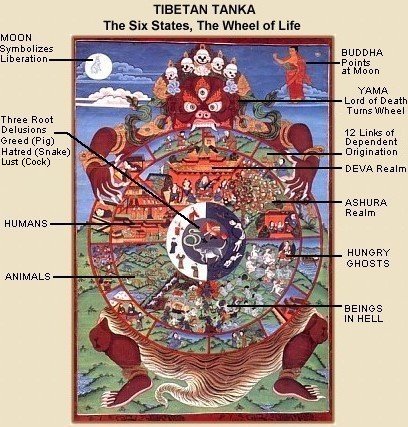

Contemplating the Matrix shows how different morality might look if we interpret the material world as a dream. Perhaps this can offer insight into the moral perspective of religious/philosophical traditions that teach that the world we experience is a kind of illusion. Buddhism, for example, has, in the past, been criticised by Christian commentators for a lack of practical action on injustice and poverty. However, Buddhism clearly teaches that we have a moral duty to help ourselves and others attain ‘enlightenment’, which roughly translates as 'waking up from the dream'.

Although the theme of awakening from illusion fits well with Buddhist and Hindu traditions the most obvious references in the film are to the story of Christ. Morpheus is a John the Baptist figure, preparing the way for the expected messiah. Neo’s official name in the film is Anderson, meaning ‘son of man’. Early on someone describes him as ‘My personal Jesus Christ’. When Neo is converted and reborn in the real world he is submerged in water and pulled out by Morpheus - an image of Christ’s baptism by John the Baptist. ‘Trinity’, the black-leather clad woman who originally contacts Neo, plays the Mary Magdalene role. Cypher, a member of Morpheus’s band who betrays Neo to the enemy, plays the role of Judas. The sign that Neo is ‘the One’ is that he can perform true miracles, not just virtual reality effects.

Early in the film Neo, or Mr Anderson, is late for his job and is called to his boss’s office. The boss tells him, in words that must surely be familiar to all of us, that his problem is that, like everyone else, he thinks that he is special and that the rules do not apply to him. The boss is asking Neo to conform to a system that is ultimately pointless. But Neo’s role in the film is as the person who really does have something special, something that transcends the rule-bound nature of the system, and not just this particular system but any system. This is also what was said of Jesus Christ. He is described as ‘the stone that the builders rejected’, or the man who did not fit in.

What is this special quality of freedom that goes beyond the rules? Is it something that only a few exceptional individuals have, or do we all have access to it? Is Christ a person or a principle?

Of course, there are also some differences between Jesus Christ and Neo. Christ might have ‘kicked arse’ in the temple when he threw out the money-lenders but he is not usually portrayed wearing shades and a long black leather coat whilst spraying the crowd with a sub-machine gun.

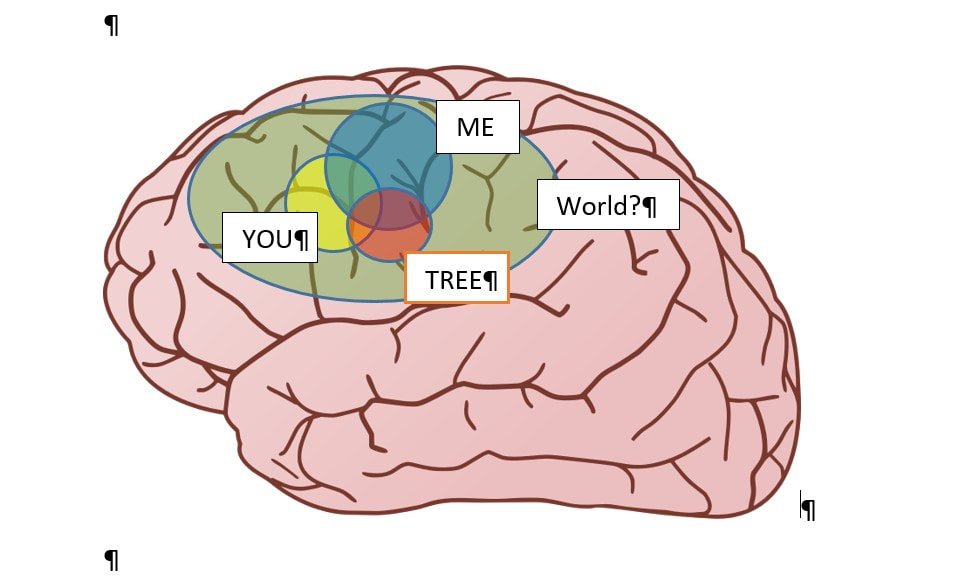

The hero of the Matrix begins with two identities, by day he is the law-abiding office worker, Thomas Anderson and by night he is the law-breaking computer-hacker searching for truth going by the name of Neo. In the film Thomas Anderson dies and the identity signified by Neo is transformed into its anagram meaning of the 'One’. Are there examples from life where an apparently virtual or fantasy identity turns out to be truer than the officially given identity? What do we make of many examples in religious traditions where one identity is said to have to die for another identity to be born?

Time out of mind

Neo and his friends enter the Matrix from outside and so they can break some of the rules that the normal inhabitants are bound by. In the fight sequences, for example, Neo can slow time down to ‘bullet-time’ – the time in which bullets can be seen as they fly and picked out of the air. Time in the Matrix is a constructed experience. God is described by Augustin as outside of time and space because he created time and space but what would time then be like for God? If our experience of time is constructed then, assuming that we are not really batteries in some future world, what would it be like to be outside of that time looking in? This is also the question of what Nirvana, the Buddhist state of awakening, is like. In the Matrix there are signs that indicate the constructed nature of time such as ‘Deja vue’ experiences, is there anything like that in our experience that might suggest that time and space are not as real as we usually think? Can experiences of eternity, described in spiritual writings but also in the psychological investigation of 'peak experiences', be explained as in some way stepping out of a virtual reality to try to view it from the outside?

The choice that Morpheus offers Neo between the blue pill, return to a comfortable sleep-walking existence in the collective dream, and the red pill, awakening to an uncomfortable reality outside of the dream, is not new in literature. This is also the theme of the trial of Socrates, where Socrates is accused of disturbing the peace with his questioning and in the end chooses death rather than a lie. In the film Cypher regrets choosing the red pill and seeks a return to ignorant pleasures such as eating steak even though he knows these to be illusions. Can ignorance be bliss? Is knowing the truth worth the sacrifice that Neo pays for it?

Virtual reality and social control

As well as religious and philosophical themes, Neo’s awakening in the film has many parallels with a more political vision of liberation. The virtual reality Matrix is a massive system of social control designed to distract humans from becoming aware of their true situation, which is that they are being oppressed and exploited by hidden masters. The band of free humans Neo joins in the sewers are an underground guerrilla movement engaging in hit and run acts of violent sabotage against the system, whilst broadcasting a message of freedom from their ‘pirate ship’.

In the film Neo is shown hiding a stash of money in a hollowed-out book with the title ‘Simulacra and Simulation'. This is the title of a book by the philosopher Jean Baudrillard. Baudrillard's main argument is that, whereas in the old days we thought of simulations as a simulation of an underlying reality, now they have taken on their own reality. Banknotes for instance, used to contain a promise to pay the bearer with real gold that was held in a bank vault. Now this promise that there is something real behind it has been dropped and money just exists free-floating as a kind of collective illusion that works only because we all buy into it.

The simulacra now hides not the truth but the fact that there is none, that is to say, the continuation of nothingness

Jean Baudrillard

'C'est aujourd'hui le simulacre qui assure la continuité du réel, c'est lui qui cache désormais non pas la vérité, mais le fait qu'il n'y en ait pas, c'est-à-dire la continuité de rien.' (p 146 Le Crime parfait. Paris: Galilée 1995)

Is the Matrix itself just another part of the Matrix?

Was bringing a Baudrillard reference into the film an ironic commentary on a big-budget Hollywood movie with a plot-line about escaping the system? Warner brothers, who made the film, are part of Time-Warner who, at the time it was made also owned the world’s largest internet provider, AOL and the world’s largest global news service, CNN. Time-Warner, now WarnerMedia, stand accused of using their multiple media interests to manipulate public tastes and opinions in order to create a market for their products. Were we all carefully programmed to find the Matrix theme interesting and to write about it in journals and blogs like this one simply to boost the profits of Time-Warner? Is the film, the Matrix, and all its sequels and spin-offs, itself just part of a Matrix- like system of distraction that fuels the profits of multi-nationals (read, perhaps: 'inhuman money making machines' ?) whilst maintaining social control?

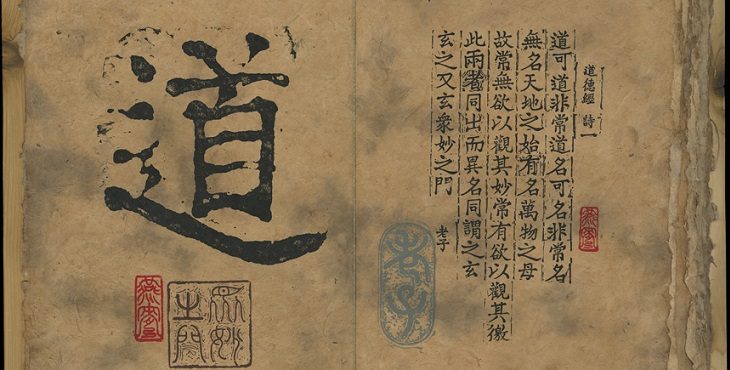

The success of the Matrix suggests that many share a dissatisfaction with the comforting illusions of collective social life and feel driven to find underlying truth whatever the personal cost. This is not new. Supposedly written by Lao Tzu around 500 BCE, the Tao te Ching contains similar sentiments:

Is there a difference between good and evil?

Must I fear what others fear? What nonsense!

Other people are contented, enjoying the sacrificial feast of the ox.

In spring some go to the park, and climb the terrace,

But I alone am drifting not knowing where I am.

Like a new-born babe before it learns to smile.

Everyone else is busy,

But I alone am aimless and depressed.

I am different.

I am nourished by the great mother.

Is the role of education to sell students versions of the comforting blue pill or is it not perhaps to provide a protected and supportive environment where they can experiment with the red pill?

References:

St Augustin, (400) Confessions. Online at https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/3296

Baudrillard, J. (1995) Le Crime parfait. Paris: Galilée online at https://monoskop.org/images/a/ab/Baudrillard_Jean_Le_crime_parfait_1995.pdf page 146

Tao Te Ching by Lao Tzu is online in many places including https://terebess.hu/english/tao/gia.html

Further reading:

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2019/mar/28/the-matrix-20th-anniversary-sci-fi-game-changer [Article in the Guardian newspaper in the significance of the Matrix]

http://www.simulation-argument.com/ [Philosphical papers on the implications of virtual reality]

https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/ctheory/article/view/14846/5716 [Disneyworld Company: a Baudrillard essay on the economy as virtual reality]

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/apr/22/what-if-were-living-in-a-computer-simulation-the-matrix-elon-musk

RSS Feed

RSS Feed