| | THE BRAIN is wider than the sky, For, put them side by side, The one the other will include With ease, and you beside The brain is deeper than the sea, For, hold them, blue to blue, The one the other will absorb, As sponges, buckets do. The brain is just the weight of God, For, lift them, pound for pound, And they will differ, if they do, As syllable from sound.[i] |

When we look at the sky or the stars we might imagine that we are looking directly at an external world but we would be wrong. It would be more accurate to say that we are looking directly at neuronal activity within our brains[2]. Neuro-science research on perception suggests that to be conscious of any part of the world requires an act of paying attention[3] but that the world we are paying attention to is already pre-processed by the brain out of a pre-conscous analysis of differences [4]. Insofar as we are looking at reality in itself we are doing so only very indirectly. Donald Hoffman, a cognitive psychologist and expert on vision, uses the analogy of the computer desktop interface to explain how perception has evolved[5]. Darwinian selection, he argues, leads to perception only of those features of reality that help in basic tasks related to survival and reproduction. The resultant model of reality that we appear to perceive directly bears no more direct relationship to underlying structures of reality than a computer desktop with images of files, and a wastebasket bears to the underlying reality of computer processes. In both cases we see what is most useful for us to see given our everyday tasks and not what is true in itself.

Figure 2: A photo of a bit of the platform at Kings Cross station: What we see is pre-processed and already pre-loaded with meaning

Realising that all experience is already pre-processed by the brain suggests that the mind is in fact to be found everywhere in the world. So talk about cognition occurring only in the brain is not wrong exactly, just misleading and paradoxical. To make sense of the paradox it might help if we distinguish between two uses of the word brain: 1) the pre-personal generative brain that creates a world for us and ourselves within it that is always already there before and behind every act of awareness and 2) the objective brain that is that squishy pink object freshly pulled from a cranium and lying on the medical lab bench in front of us.

This duality of the brain, brain as subject and brain as object, is a version of the fundamental duality between subjectivity and objectivity found everywhere in experience. Martin Buber begins his 1937 book ‘I and thou’ with the claim that ‘To man the world is twofold, in accordance with, his twofold attitude.’[6] This twofold attitude, Buber continues, is to objectify the world in the ‘i-it’ attitude and to subjectify the world in the ‘I-thou’ attitude. For Buber one can objectify people, turn them into numbers, treat them all as equal individual units, or one can in a sense subjectify them, that is treat them as people, as sources of meaning who need to be listened to with respect. Buber’s I-thou attitude is the basis of dialogic pedagogy. But Buber went further than most dialogic psychologists in claiming that one could take an I-thou attitude and, in a sense, subjectify the world as a whole and non-human animals and even objects within it. He has a famous account, for example, of learning from engaging in dialogue with a tree[7]. One way to make sense of this dialogue with objects is to realise that every apparent object, like the tree, is already pre-processed by the pre-personal brain and so is pre-loaded with meaning (see Figure 2).

Group thinking

One problem that I have with classical cognitive psychology associating mind too closely with the physical brain, - I mean the little pink object weighing about 1.5 kilos - is that this makes it hard to understand group thinking. Realising that mind is everywhere makes it easier. Assuming that my brain and your brain and ape brains in general have evolved in pretty much the same way explains why we inhabit roughly the same world of experience. If I (as physical body) see a tree in a landscape then you (as physical body) will see the same tree from a slightly different perspective. When I look out at the tree I am also looking at the inside of your brain and you are already looking at the inside of mine.

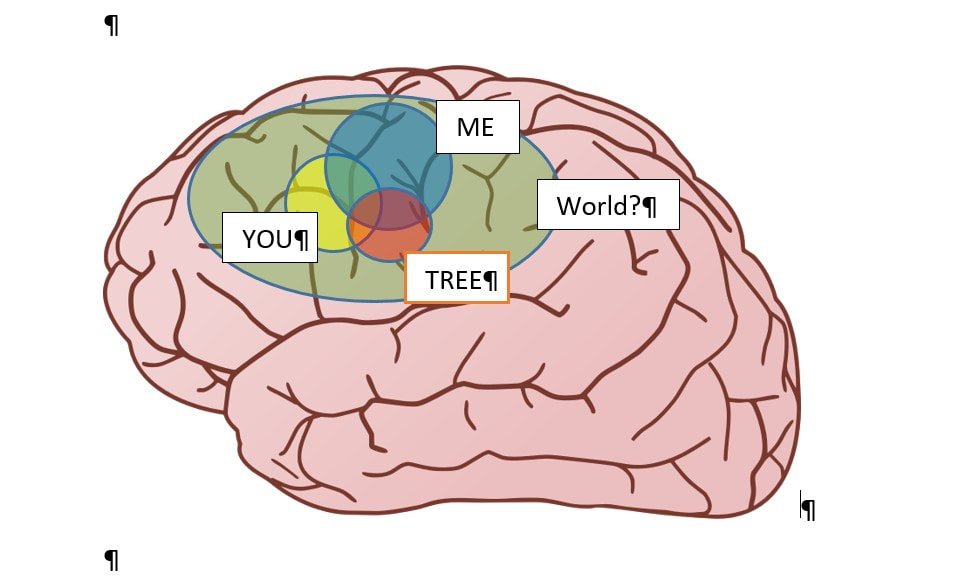

To understand what is going on in group thinking we need to invoke the two levels of brain referred to earlier. The pre-personal generative brain or brain 1 produces a sort of image of myself walking through a landscape just as it produces an image of you walking through the same landscape. This means that, for the pre-personal brain, my status is not that different from yours as just another sort of image generated by the pre-personal brain and, in a sense, within the pre-personal brain. Group thinking is possible precisely because we inhabit a shared world and we move within that shared world in relation to each other[8].

The Chiasm

Like most labelled brain images Figure 3 is potentially very misleading. It is not helpful to imagine that things like me, you, trees and the world are to be found as objects ‘within’ a brain. The brain is not really like a computer and it does not really store representations of the world[9]. It is more that the brain works closely with the body to do things. The body-world is ‘enacted’ each time we reach out to grasp something or each time we look at a tree in a landscape. The mind and the world are both only to be found bound up with the actions that constitute experience. Ideas about the separateness of the mental and the physical are misleading ideas that form in the wake of experience[10].

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, a professor of psychology at the Sorbonne for many years as well as a phenomenologist philosopher, struggled with ways to understand the paradox of experience or how come we think that we have both a mind (subject) and a body-world (object). He explored how pre-personal processes produced both a body image and a world image[11]. The world, for Merleau-Ponty, was never simply objective but always the world as experienced. He called the world ‘the ensemble of my body’s routes’[12].(VI 246). Against the crude dualism of Descartes who claimed that there is mental stuff and physical stuff, Merleau-Ponty’s careful analyses of perception show that the mental and the physical are closely bound up together in each act of experience.

Merleau-Ponty suggested an experiment we can all do to explore how subjectivity and objectivity (the mental and the physical) are bound up in even the simplest experience. If I touch my left hand with my right hand I can experience my right hand touching or, with a shift of perspective, I can experience my right hand being touched. Am I now an object or a subject? Mind or matter? And where is the gap between these two?

Each experience seems located in a pre-given world of space and time. But if we ask ‘where is the world’ we see that it is generated out of thousands of these kinds of touching and being touched type experiences. When I touch the table, the table touches me back. I am on both sides of the experience. The same when I look at the horizon. The horizon looks back at me and locates me in the centre of it. The world of space and time that I experience is constructed through perceptual acts and does not exist separate from them. So where exactly is the gap (écart) between my right hand touching my left and my left hand touching my right? The gap is generative of space and time. It is not itself located in space and time since it is that which locates. And yet at the same time it appears to be located here right in front of me where my right hand is touching my left?

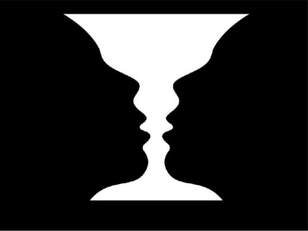

Mearleau-Ponty develops a new ontology from his analysis of the apparent paradox of the fact that experience is always already located and yet it also does the locating. This new ontology is sometimes referred to as the ‘flesh’ but is based on the figure of the ‘chiasm’. The chiasm is a term from rhetoric referring to the reversal of subject and object in a sentence. ‘I see the world: the world sees me’ is a chiasm. Each act of perception involves a figure ground chiasm whereby the figure, that which is seen or touched, stands out to define the world around it while, at the same time, the world crowds in to define and locate the figure.

Merleau-Ponty was particularly interested in analyses of art and language showing how bits of the perceptual world could separate out from the background to become signs and symbols with which to think the world by reflecting back upon it. Thought is never pure thought for Merleau-Ponty but always bound up with bits of the material world, using signs, syllables and sounds. At the same time matter is never purely material but always richly charged with invisible meaning and only standing out as a ‘thing’ because it speaks of an invisible idea. In every bit of the ‘flesh’ the visible and the invisible, the subject and the object, mind and matter are always closely intertwined in a chiasmic relationship - that is in a relationship of mutual envelopment and reversibility.

In the poem above by Dickenson the physical brain becomes a model or metaphor for the whole world. But for Merleau-Ponty perception pointed to the universal metaphoricity of matter. For Merleau-Ponty everything can become taken as a metaphor for everything else and this metaphoricity of the world is the medium of thought and the origin of ‘mind’. He writes:

The “World” is this whole where each “part,” when one takes it for itself, suddenly opens unlimited dimensions— becomes a total part. (VI p218)

This blog began with the question ‘where is the mind?’. It is not to be found just in any one little bit of the world – the brain for example - but in every little bit of the world. Everything is already a kind of thinking and when we think properly we participate in that larger thinking, the thinking of the world. Thought or mind is as much the thinking of material things as it is the thinking of humans since material things and humans are always already thoughts within a larger thinking that is not simply ‘my thinking’ or ‘your thinking’ but a thinking in general that possesses us as much as we possess it. But when we ask ‘where is this thinking?’ we face a problem because the world is as much a product of thinking as it is a location of thinking. Space, time and matter are not a kind of shoe-box given before we think – they are the medium with which we think.

Mealeau-Ponty refers to ‘that primordial property that belongs to the flesh, being here and now, of radiating everywhere and forever’ (VI, 142). He points out that we sometime think we might get a better view of the world if we did not have a location within it but this is a misunderstanding. A view from nowhere would be no view at all. Being embodied is what enables us to see, touch, taste, smell and think the world. It does not trap us within a world but gives us a perspective. This understanding of embodied perception gives us a clue as to the location of mind. Mind, or ‘minding’ in the sense of active embodied thinking, is always to be found both ‘here and now’ and also ‘everywhere and forever’. It is never just in the middle, but always both extremes at once because mind is only located ‘everywhere and forever’ by virtue of being located ‘here and now’. The moment I open my eyes or open my mind to think I find myself both ‘here and now’ on one side and looking out ‘everywhere and forever’ on the other side. Where we tend to think we are, the images we construct of our self identity or the models we construct of the world, models that we then often imagine that we are trapped within, are born out of the continuous dynamic tension between these two extremes - being everywhere and forever by virtue of being here and now.

[1] See her poems at http://www.bartleby.com/113/1126.html

[2] Here are two interesting videos on perception making this point https://youtu.be/yxa85kUxBDQ with Ramachandran and https://youtu.be/C8k-lrJrldw with David Eagleman

[3] DeHaene, S. and Naccache, L. (2001). Toward a cognitive neuroscience of consciousness: basic evidence and a workspace framework. Cognition, 79, 1–3: 1.

[4] Poort, J., Raudies, F., Wannig, A., Lamme, V. A., Neumann, H., & Roelfsema, P. R. (2012). The role of attention in figure-ground segregation in areas V1 and V4 of the visual cortex. Neuron, 75(1), 143-156.

[5] https://www.ted.com/talks/donald_hoffman_do_we_see_reality_as_it_is. While Hoffman has some controversial views involving the direct applicability of quantum theory the interface view of perception that I refer to here is not very controversial.

[6] Buber, M. (1958/1937). I and Thou (Second Edition, R. Gregory Smith, trans.). Edinburgh: T & T Clark; available online as a PDF of you search a little.

[7] http://www.rupertwegerif.name/blog/dialogue-with-a-tree

[8] Gerry Stahls careful analyses of group cognition shows how it is more about moving within a shared world than about building shared internal schemas. Stahl, G. (2005). Group cognition in computer‐assisted collaborative learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 21(2), 79-90.

[9] Epstein, R. (2016). The Empty Brain: Your Brain Does Not Process Information and It Is Not a Computer. Aeon Essays. Google this excellent essay to find out more.

[10] Chemero, A. (2011). Radical embodied cognitive science. MIT press. See also his video at: https://youtu.be/dZn9Y1jqGls]

[11] Merleau-Ponty, M. (2013). Phenomenology of perception. Routledge.

[12] Merleau-Ponty, M. (1968). The visible and the invisible: Followed by working notes. Northwestern University Press.

BTW most of these arguments can be found in a different form in Wegerif, R. (2013) Dialogic: Education for the Internet Age, Routledge pp 155-157.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed