Switching perspective or seeing things from a different point of view, is a key ‘mechanism’ in my dialogic theory of education – and probably for any dialogic theory of education - but what exactly does this mean? I do not think it is quite as simple as it may at first seem.

1)Point of view in a shared objective space

A popular image of a switch in perspective is to see a landscape from one point of view and then to move to see it from another point of view. Piaget, being Swiss, developed a task with mountains to see when children could see things as if from a dolls point of view placed somewhere else in relation to the landscape. Younger children who could not describe what the doll could see but only what they could see were said to be egocentric. Those who could describe the scene from the point of view of the doll were capable of a more decentred understanding indicative of cognitive development in general.

2)Point of view when there are many worlds of experience

Piaget’s experiment assumed a single objective space such that what was seen from each perspective was always the same. This mostly works for seeing from the other side of a mountain on a sunny day but is not strictly true of every perspective switch in a dialogue.

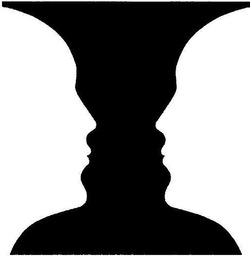

Last year a Twitter war about the colour of a dress, - is it white and gold or blue and black? – drew attention to the fact that people see things differently.

If people can even see a publically accessible image of a dress so differently it is not surprising that their understanding of concepts like justice, truth and beauty and so on will be very different. Each person is in fact the centre of their own unique world formed by their own unique history and, indeed, their own unique biology. As the social anthropologist Margaret Mead put it, ‘Always remember that you are absolutely unique. Just like everyone else’.

The idea that there are multiple different worlds of experience or ‘empirical realities’ might sound rather subjective and not very scientific. However, a version of this theory has been the orthodoxy since Einstein’s theory of relativity about one hundred years now. According to Einstein’s theory there is no universal simultaineity or experience of ‘now’. What seems to be ‘now’ is relative to the position and velocity of the observer.

Of course most people most of the time will share enough ‘spacetime’ in common to be able to communicate. Similarly, even though everyone has a unique brain generating apparent reality for them in a unique way, most of us share enough overlap in our perceptions to be able to communicate. In both cases this is because we do in fact share the same ‘objective reality’, just that this is at the transcendental level of underlying structures revealed by science – the formulas of relativity theory for example - and not necessarily at the empirical level of our experience in which everyone’s ‘now’ is a bit different from everyone else’s.

In this situation where each is the centre of their own unique, if overlapping, world, a switch in perspective is more complex than simply changing position with someone on the other side of a mountain. Some effort needs to be made to re-construct the world as it appears and as it feels from a different perspective, building up from the shared structures that come with our basic physical humanity without being able to assume any shared cultural frame of reference.

3)The basic transcendental/empirical perspective switch

When I first learnt to create simple web-sites using HTML coding language I was delighted to find that simply typing a simple hexadecimal number in my script could change the colour of my whole web-site into any known colour. I tried different codes out in the script, clicked save, then re-loaded to site to see that it had all gone golden or aquamarine or black. On the one hand I was looking at the underlying code that shaped my experience, on the other hand I was enjoying the experience. The two sides, the code and the experience, did not meet. It is not possible for me to see both at the same time. In this kind of perspective switch there is no continuity of experience but a gap. Either you are on one side, viewing the code, or on the other, viewing the experience.

Changing the colour on a web-site might not seem very significant but imagine I was programming immersive virtual reality experiences with cyber googles, cyber gloves and a multidirectional treadmill. I could switch perspective from code on the one side to lived experience on the other.

This is what science does when it moves between the transcendental code, like quantum theory, and the empirical phenomena that are shaped by that code, like ‘observing’ the traces of sub-atomic participles. Weaving between the underlying code and the surface experience is not just a feature of natural science but also of social science. Underlying invisible social structures shape experience and emotion making some things seem obvious and others seem impossible. If we want to improve human life as educators we need to understand the way in which experience and feelings are programmed in order to change the programming for the better.

In the ‘Thinking Together’ research programme we found that classroom talk was shaped by implicit assumptions or ‘ground rules’ that did not always lead to the best or happiest results. By examining these and re-shaping them through guided educational experience we were able to change the culture of the classroom in ways which led to different experiences. On the whole teachers and students reported happier classrooms where problems were resolved through talking which had previously led to conflict.

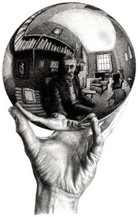

4)Reversal of perspectives in a dialogue

The switch in perspective to see oneself as if through the eyes of another is rather more like the empirical/transcendental switch described above than like imagining what it is like to see from the other side of the mountain. This is because, in a dialogue, the other person is not just another body in a landscape, like the doll in Piaget’s experiment, but she is my outside as I am her outside. Moving between these two perspectives is switching between insides and outsides of experience with no continuity of the kind you might get with camera tracking as you move from seeing the mountain on one side to seeing it on the other. In fact there is a gap between these two perspectives exactly as there is in switching from writing the computer code to experiencing the effect of the computer code.

Looking out from the inside I am the ‘transcendental’ gaze that constructs the other as an image in my field of vision. My invisible categories and underlying assumptions will shape her as an object. Her accent will locate her in a social field. Her clothes, her choice of words, her hair-style etc, all will converge on a representation that sums up who she is. BUT in this case the other is also my outside. She contains me and judges and constructs me as an image in her field of vision. In entering into dialogue with her I immediately surrender part of my sovereign right to construct her and allow her the right to, at least partially, construct me. In order to dialogue I need to be able to ‘incarnate’ her on the inside of me. I need to take her seriously. Even to hear her voice I need to reconstruct her position to make sense of what she is saying and in doing that, in making an effort to actually understand what she is saying to me, I have to allow her to be a transcendental other, someone who constructs meaning as I do, someone who is the centre of her own world, and in that world, in the world she constructs, I find myself located as one amongst others.

5)Dialogue with the outside

Dialogue with the outside, of what I call elsewhere, the Infinite Other, is not symmetrical. This other contains me but I do not contain it. It seems to me to take the form of a horizon around me but I know that it exists also beyond the horizon. When it talks to people I notice that they are often tempted to give it a form. If, for example, it points out that they did something wrong even though no-one else has noticed, they might think of it as the voice of God or an ancestor. When it points out insights that they did not see, that no-one had seen, they might think of it as a like a spirit guide or, in a different context, even like the future community of scientists able to see and understand much more than their limited contemporaries (Habermas invokes this future community). But whatever form the Infinite Other seems to take it is obvious that it is not limited to that form but transcends that form because its essential nature is not to be pinned down.

When I have made this argument in conferences people sometimes say to me that ‘that is just people talking to themselves, it is their voice that they hear’. In other words what people take to be the voice of the outside is really just them. I can see why we want to say that what appears to people as the voice of the outside is not really outside them because physically it comes from within their brains. I am not completely convinced by this assumption of a physical frame locating thought within individual brains as I explain elsewhere (Dialogic: Education for the Internet Age, download pdf and search on neuro) but playing along with it for a minute there is a reason why we need to distinguish our own voice from the voice of the outside. This came out most clearly in an unexpected side-effect in experiments on ‘Aha’ creativity described by Kounios and Beeman. A clever experimental design enabled Kounios and Beeman to track sudden insight solutions to problems as these arose in the brains of participants. Before the insight appeared there was a desire to close the eyes or blink more frequently linked to specific patterns of brain activity indicative of inhibiting some areas. In other words, they conclude, in my interpretation at least, that in order to allow the often weak signals of insights to come through we need to supress the stronger signals associated with the activities of what we take to be ourselves in order to allow voices to speak that appear to us to be ‘other’ [Kounios, J., & Beeman, M. (2009). The Aha! Moment the cognitive neuroscience of insight. Current directions in psychological science, 18(4), 210-216.]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed