Relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.

‘in this era of post-truth politics, it's easy to cherry-pick data and come to whatever conclusion you desire’

‘some commentators have observed that we are living in a post-truth age’

Applying the term ‘post-truth’ to the ancient phenomenon of false news links it to the Internet and to post-modernism. A popular version of ‘postmodernism’ might be that there are no facts, only interpretations. Perhaps using the term ‘post-truth’ could be a sly way of kicking postmodern professors? Perhaps it is a way of saying: ‘you have been claiming there is no truth for years – now your words have finally come true and I bet you hate it!’.

The link between the idea of postmodernism and the Internet is so close it could be called umbilical:

‘our online experience embodies many of the underpinnings of Postmodernist theory. In the internet we find a system composed of innumerable narratives and voices, where information lacks fixed meaning and context is easily discarded. Our personas, too, are disposable, a patchwork of opinions and connections whose tethers to reality are in constant doubt. Relativism, plurality, decontextualization of information, destabilization of “reality” and identity: these are decidedly Postmodern concepts. In looking at the salient aspects of our online experience, then, we do indeed see Postmodernism in action, its tenets “made real by the internet.”’ (http://artfcity.com/2011/10/03/baudrillard-did-the-internet-kill-postmodernism/)

Perhaps the contrast between truth and ‘post truth’ is a version of the contrast we tend to draw between reality – experience in the physical world - and ‘virtual reality’ – our experience online? Perhaps ‘post truth age’ is a version of ‘Internet age’?

The term ‘post truth’ implies a contrast, ‘simple truth’ perhaps, that straight-forward no-nonsense old-fashioned truth we used to get told by priests, aristocrats, professors and politicians whom we could trust. Simple facts and not interpretations. The sort of things that experts know and write in text-books or broadcast in BBC voices while wearing jackets and ties. The contrast implicitly being made with the term 'post truth' is not only between ‘true’ and ‘false’ but also between traditional media and new media. ‘True’ news, implicitly, is likely to result from proper procedures, from using trusted authorities, from the practices of regulated broadcast and print media outputs. ‘Fake’ news is associated with the untrammelled access to broadcasting offered by the Internet such that anyone, however ignorant, stupid or malign, can post claims that can quickly reach millions. Traditional one-to-many media such as print and television require physically located technologies, a printing press or a TV studio, which has to be owned and can be regulated and, in extremis, shut down. The Internet cannot be so easily regulated, controlled and shut down.

In 1938 a radio broadcast of a dramatised version of H.G.Wells 'War of the worlds' in which the Martian invasion of the Earth was presented in a series of news broadcasts led, it has been claimed, to some panic and a widespread concern that the planet Earth really was being invaded from Mars. Since then radio audiences have become more adept at telling real news from fictional news. Perhaps the prevalence of 'post-truth' and 'fake news' is a product of readers who have been educated to accept the truth of what they read and hear through one dominant set of media practices, one-to-many media such as print text books, now having learn new practices in order to take a more critical and co-constructive attitude towards the truth.

The 'true' news and the 'truth' that is implicitly presumed to have existed before the 'post-truth' age was always already biased and always already should have required a critical and participatory reading. Delivering news via the Internet requires a shift of readers from passive acceptance to active criticism and participatory co-construction which is potentially a good thing for democracy even if, initially, the failure to make this shift, leads to the apparently harmful effect of believing and sharing false news. Education here might have an important role to play in teaching people how to read and participate on the Internet.

Two kinds of education

It is sometimes claimed that education is not a solution to violent extremism since so many terrorists have turned out to have a university level education. But is that true? Yes and no. Martin Rose argues that the issue is not the amount of education but the kind of education.

‘Far from being uneducated, a large number of violent extremists are highly qualified. One study from 2007 found that 48.5% of jihadis recruited in Middle East and North Africa ('MENA') were university graduates, and 44% of those had studied engineering . Furthermore, from Islamists Osama Bin Laden, Mohammed Atta and Sousse killer Seifeddine Rezgui (all engineering graduates) to ‘Unabomber’ Theodore Kaczynski (a PHD and lecturer in Mathematics), anecdotal evidence suggests prominent terrorists of some ideologies particularly perhaps those that could be characterised as being on the extreme right of the political spectrum, disproportionately studied technical subjects rather than graduating from religious or political courses.’

As Howard Jakobson puts this same point ‘show me the jihadist with a well-thumbed copy of middlemarch in his back pcoket’

The problem seems to be that in many places science and engineering, technical subjects, that ought to be taught as creative, critical open-minded explorations of possibilities are actually taught as if there were simple truths, black and white, right and wrong. This is ‘monologic’ teaching where monologic means that there is just one voice, just one true perspective. This kind of ‘education’ seems particular common in the Middle East and North Africa but is also common in secondary schools in the UK, especially in science subjects. People taught what to think, what is right and what is wrong, but who have not been taught how to think, are dangerous people, prone to believing that they know the truth. The sort of people who make a mess on the Internet.

The alternative to monologic education is dialogic education, education into dialogue, into an idea of the truth as not simple but as a direction of learning through open minded exploration in which challenges and alternative perspectives are to be respected as they are likely to be the sources of new understanding. Although this kind of education is typical of arts subjects it is also entirely appropriate to maths and science subjects as it reflects the real truth of maths and science: open-ended inquiry through dialogue and exploration.

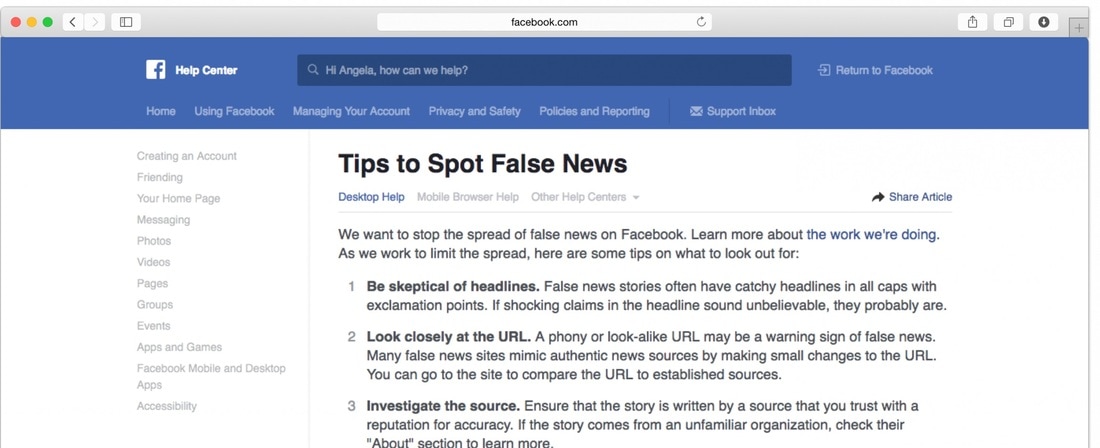

The claim that false news spreading on Facebook influenced the outcomes of elections in the USA led to a response from Facebook on the form of a tool giving users tips on how to read Facebook posts and how to spot fake news stories and the strong advice not to pass them on through sharing. This is essentially basic education in critical thinking. In addition software was developed to spot potential fake news stories and label these with a red warning to users to be cautious and not to share.

Education for democracy

Socrates’, an oral thinker, complained about writing. He pointed out that people can now borrow scrolls and make speeches that have the appearance of truth but no real substance because, if you question them, they quickly reveal that there is no intelligence behind the fine words. Here is describing how writing easily supports a false ‘monologic’ version of truth and a monologic education into reading out scrolls without thinking for yourself. The modern world has been shaped by the almost magic power invested in key texts, from core religious texts to law codes and more recent universal declarations of human rights. This focus on texts has largely swept aside Socrates’ ideal of truth emerging from intelligent dialogues, replacing this ideal with an image of truth as something more like ‘the laws of physics’ as written down in science text books (Toulmin, 1990). Spoiler alert: there are no fixed laws, truth is not a text, is a living dialogue. The recent concerns over ‘post-truth’ are perhaps a symptom of moving from one regime, print-based truth, to another conception of truth more appropriate to the Internet Age. The advent of the Internet only has the potential to change what we mean by truth again if it is combined, just like the regime of literacy before it, with a universal project of education. Literacy is a communications technology that does not work without education. Perhaps the same is true of the Internet. The Internet without education could lead to stupidity and tribalism. The Internet with education might be the beginning of a new age: not so much a ‘post truth’ age as a ‘new truth’ age or an ‘everyone involved in creating truth together’ age.

An introduction to dialogue programme is an essential precursor to blogging. This teaches ground rules for effective online dialogue. The practical outcome of these activities can be summed up in four prompts that are then repeated throughout the online web-site.

Experience: ‘give readers in insight into your life, explain why things are important for you.’

Clarity: ‘will your post be clear to someone from another country?’

Questioning: ‘Ask good questions that prompt the writer to explain their ideas more deeply’

Reflecting: ‘Make connections between your post and others’ and show that you are thinking about what you read’

This is not so different from the sort of ground rules for dialogue taught by the Thinking Together programme I once helped to develop with Neil Mercer and Lyn Dawes (http://thinkingtogether.educ.cam.ac.uk/) .

Of course any particular set of ground rules can be challenged but those who have learnt how to dialogue are open to those challenges and able to learn from them so that their practice develops and they themselves develop. The key thing to be learnt is how to engage with other views constructively without violence, from that seed everything can grow.

As well as the pedagogy the success of the Generation Global platform depends on technology design. Like Twitter the interface enforces a certain length of message, not too long so that they overwhelm the dialogue (no more than 800 characters) but also (unlike Twitter) not too short (not less than 30) so people can’t just pile in with unreflective likes or dislikes but have to say something. The moderation algorithms have to be powerful to pick up abuse. A culture of reporting is encouraged and any post reported as suspect is instantly suspended until moderated. Students’ blog together in small groups automatically assigned from varied locations and maintained for long enough to create a sense of community and trust. As well as prompts to support ground rules openings can be suggested in case students are not sure how to break the ice or how to phrase what they want to say. Awareness tools reflect back to each student how they are communicating, how much reflection, how many questions and so on. In short we are talking here about education as design, building on decades of experience of how to design for collaborative learning on the Internet.

Generation Global tends to focus on issues related to global citizenship but similar approaches have been shown to be effective in teaching almost any and every subject: challenge based science, maths , enterprise and all the many subjects now taught and learnt collaboratively online – the difference is that, learning this way, children and young people are also learning how to talk to strangers and not to be afraid. Learning this way they are also learning how to prepare for a future where science, in the broad sense, is not just about passing exams and ‘knowing stuff’ but about working together to overcome real challenges and to build something new.

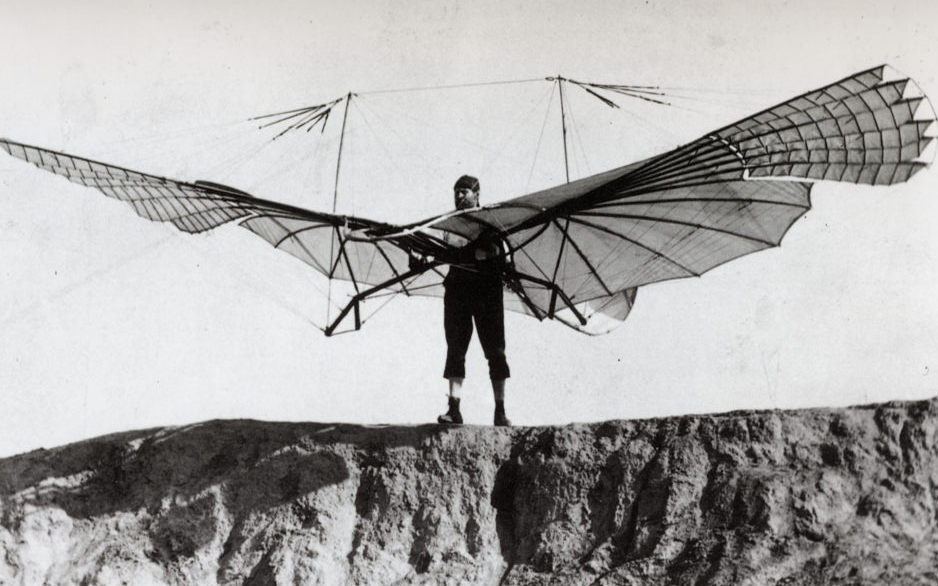

We are still in the early days of the Internet Age, still learning how best to design ourselves through education so as to make best use of the potentials now open to us. At this juncture in human history, with the advent of the Internet and our general confusion about what to do with it, what we need is not just the kind of research that is content to describe reality or educational research that helps to make now outdated print-based education systems work better at producing increasing irrelevant goals and increasingly irrelevant people – what we need is the kind of research that creates a new and better reality. A possible model to follow here is the way in which aviation began in sustained design-based research where the only certainty was the aim, building machines that could enable humans to fly (O’Neill, 2012). We know roughly what we want now, which is global democracy – making decisions on the basis of dialogue and not on the basis of fear or violence - but we do not yet know how to get there. The aim for educational research should be to design educational technology systems to achieve this aim, evaluate their impacts, refine the designs, try and try again and eventually, like the aviation pioneers over one hundred years ago, we might have a system that flies.

O'Neill, D. K. (2012). Designs that fly: What the history of aeronautics tells us about the future of design-based research in education. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 35(2), 119-140.

Toulmin, S. (1990). Cosmopolis: the hidden agenda of modernity. New York: Free Press

RSS Feed

RSS Feed